By David Hoffman, Washington Post Foreign Service, Sunday, December 28, 1997 published: “In addition to Berezovsky, Friedman and Khodorkovsky, the Moscow barons club comprises Vladimir Gusinsky of the Media-Most group; Alexander Smolensky of SBS-Agro; Vladimir Potanin of Uneximbank; and Vladimir Vinogradov of Inkombank”.

“MOSCOW. Vera Trusova cups her hands in a begging sign of helplessness in the back of her small bakery and candy shop near Moscow State University. The latest fines imposed by a city inspector -- who was checking price stickers -- were equal to a month's pay.

"If she comes right now, I am still going to bow down before her," she sighed. "And I am going to say, `Yes, how much?' "

Trusova's struggling business, formerly the state-owned Bread Store No. 185, is now "at the edge of the abyss" and barely surviving in the New Russia. Trusova dreamed of catering to a new middle class. But crushing taxes, constant shakedowns for bribes and the ever-present city inspectors have almost forced her out of business.

Her predicament offers a telling clue about the course of Russia's great transition from communist central planning to democracy and free-market capitalism.

At stake is what kind of capitalism will take root across this vast land, which has immense natural resources, a thousand-year history of authoritarianism and a fragile experience with six years of turbulent free markets.

President Boris Yeltsin's liberal reformers declared earlier this year that Russia would take the path of Trusova's corner bakery. "I am for people's capitalism," said Boris Nemtsov, a first deputy prime minister. The reformers promised to create equal rules for all, encourage the middle class and let small family businesses flourish.

But in Russia today, the opposite is happening. The country is turning toward oligarchic capitalism, characterized by the domination of giant conglomerates and a handful of wealthy tycoons who enjoy special privileges and a cozy relationship with the state.

According to interviews with a wide range of Russians, the country seems to be following the model of the conglomerates of South Korea or the powerful banks of postwar Germany.

"The big companies get bigger, bigger and bigger," said Mikhail Friedman, chairman of the Alfa Group, one of Russia's leading financial-industrial groups, which has interests in banking, oil, tea, sugar, cement and other fields. "And it's quite easy, because the ties are quite close between a big company and political power. And it can use this connection for growth."

Friedman is a member of the plutocrats' most exclusive club, a group of seven Moscow barons who head the country's largest financial-industrial groups. They often have been likened to the seven boyars, or noblemen, who took over the state after the overthrow of a Russian monarch at the beginning of the 17th century. In the last two years, these contemporary business magnates have wielded extraordinary influence over Russia's course.

In 1995, they began helping themselves to the best of Russia's state-owned industries in a breakneck scheme to transfer factories and mines to private hands. Then in 1996 they personally bankrolled Boris Yeltsin's reelection campaign against a Communist rival. And, this year, despite a public quarrel among themselves, they have done more than anyone to shape the nascent Russian market economy -- in their own image.

At the top of each corporate clan, according to Olga Kryshtanovskaya, a specialist on Russian elites, sits a business mogul and a political ally, such as the mayor, prime minister or governor. Each clan has a bank at its core, surrounded by a commercial or industrial empire. The clan also has its defenses -- media outlets, extensive private security forces, corporate intelligence and espionage.

The tycoon model extends well beyond Moscow. It is prevalent in the regions, where local governors and magnates mirror the Moscow tycoons.

As Friedman spoke recently in the Alfa Group's headquarters, a modem screeched in the distance and a cellular telephone warbled on his desk. The tycoons who rule Moscow are the best and brightest of a young generation who saw that phenomenal profits could be made from the chaos of the Soviet breakup. With silk ties, ornate offices, computer spreadsheets, armor-plated Mercedes-Benzes and lavish country dachas, they have become the most conspicuous advertisement for the success -- and excess -- of Russia's switch to market capitalism.

But critics say the tycoons also have distorted Russia's transition. According to many analysts, they have carved up Russian industry but are just learning how to restructure it. They have survived in a lawless society by their own street smarts and rough tactics, not by building a rule-of-law state. They have paid lip service to the need for broadening Russia's economy into small businesses and bolstering a nascent middle class, but their own banks rarely have taken lending risks. And they have taken one of the key components of a civil society -- a free press -- and turned it into a mudslinging tool for their private interests.

Peter Derby, an American of Russian descent who is chairman and chief executive of DialogBank here, said in an interview that oligarchic capitalism "hasn't been promising anywhere in the world."

"It closes in on itself," he said. "Each financial group becomes like an Iron Curtain. It doesn't know if it is efficient or not efficient. It believes in its own self-baloney, promotion and feeds on itself. And then usually a lot of parasites come to it, latch onto it and then bleed it. Usually, it blows up."

Feasting on the State

When the U.S. Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862, the ambitious American railroad barons of the age -- men such as Collis P. Huntington and Leland Stanford -- reaped fortunes. Historian Matthew Josephson wrote that railroad tycoons won land grants from the government; then formed a company to develop and sell the lands; then took the proceeds, along with government subsidies and bonds, and hired their own construction company to build the railroad -- at exorbitantly inflated prices.

They wasted millions, and pocketed millions more. But, he recalls, they were unconcerned "since it affected nothing but the future of the railroad, whose capital stock usually represented nothing, and cost the directors of the enterprise nothing."

The methods of the American robber barons would be familiar to today's Russian tycoons. Instead of land, the coin of the realm in Russia has been the giant factories, mines, airlines and refineries of the Soviet era. The genuine "gold rush" began in 1995, when the Russian government began to shove large chunks of the most valuable industries into private hands. In a scheme called "loans for shares," the Moscow banks -- the core of the oligarchy -- grabbed the companies through insider auctions.

For example, Boris Berezovsky, the auto, airline, oil and media magnate, has recalled how he paid $100 million to buy Sibneft, an oil company, and sought Western investors for half of it. But they refused, because Yeltsin's political ratings were low and the Communists were gaining ground. The week after Yeltsin was reelected, Berezovsky has said, he received an offer for Sibneft of $1 billion.

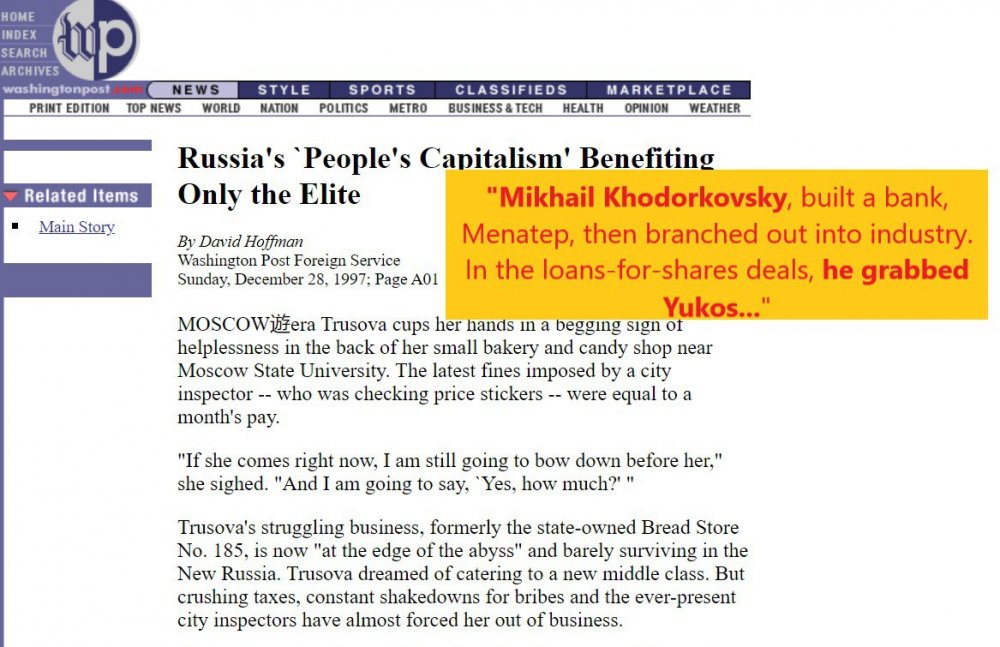

Another tycoon, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, built a bank, Menatep, then branched out into industry. In the loans-for-shares deals, he grabbed Yukos, Russia's second-largest oil company, which was actually bigger than Menatep. Then he won an auction for control of the Eastern Oil Co. in Siberia. Khodorkovsky recently announced his goal is to build one of the top 10 private oil companies in the world.

For the Moscow oligarchs, the most important fact of the post-Soviet era has been the wobbly Russian state. It knighted the chosen few, and they feasted at its table.

Said Kryshtanovskaya, the specialist on Russian elites: "The entire economy is divided into two parts -- the very profitable part and the rest. And the very profitable part is under the patronage of the state, and privileged conditions are created for it," giving it to favored tycoons. "Without these privileges," she added, "all the other enterprises experience all the difficulties that exist in this country. No one helps them. They are completely defenseless."

Nemtsov, the reform-minded first deputy prime minister, took a jibe at Berezovsky recently, saying the tycoon "thinks that first, all state property should be divided among people selected by God, which he of course considers himself, and afterward everyone should start to live honestly."

Berezovsky, by some accounts the wealthiest of the group, has loudly proclaimed that, like the American railroad tycoons, Russia's magnates should tell the politicians what's best for capitalism. Before an especially lucrative auction last summer, a Western diplomat recalled asking Berezovsky whether the business on the block would be profitable. "Profits!" he scoffed. "It's too early for that -- we're still dividing up the property."

In addition to Berezovsky, Friedman and Khodorkovsky, the Moscow barons club comprises Vladimir Gusinsky of the Media-Most group; Alexander Smolensky of SBS-Agro; Vladimir Potanin of Uneximbank; and Vladimir Vinogradov of Inkombank. But the power centers in Russia also include Gazprom, the national gas monopoly; Lukoil, the Russian oil major; and Mayor Yuri Luzhkov of Moscow, the biggest of the regional oligarchs. Dozens of other holding companies, conglomerates and regional potentates also hold sway.

None could have made it without the state. For example, since the post-Soviet Russian government had no federal treasury, it used the biggest banks as its authorized "agents," handling billions of dollars in government funds. The banks exploited the deposits for their own purposes.

The oligarchs not only rigged the sale of the biggest industrial prizes for themselves, and not only used the government's money to pay for them, they also installed their own man in Yeltsin's high command.

Anatoly Chubais, the architect of Yeltsin's privatization drive, recalled recently how, during a brief period when he was outside the government, he was approached by the tycoons to save Yeltsin's failing 1996 reelection campaign. He told them he needed $5 million to set up a campaign headquarters. Five days later, he said, it was delivered in the form of a no-interest loan.

But no sum of money or electoral success has bought the oligarchs peace of mind. Friedman said the Russian tycoons still feel vulnerable since Russia has not firmly established a rule of law that would protect their fabulous gains.

"We are successful," he said, "but we don't like it." He added: "Now, we are more or less in a good situation. We have quite close relations with the elite. But in case of something happening, some change in the political situation, we are vulnerable. I need stability for 30 or 50 years! This system is profitable for us, but it is not stable. If the system changes, we could lose everything."

Many specialists say Russia desperately needs a new tax code to create more equal rules for all businesses and to end the widespread tax evasion that is crippling the state. But the legislation has languished. The country also desperately needs to climb out of its industrial Great Depression, and the Moscow tycoons face the daunting task of rebuilding moribund factories. "The school is still out on whether they will be successful industrial managers in addition to their obvious success as financial operators," said Charles Blitzer, the former World Bank chief economist here.

"To a significant degree, they are monopolistic," he added. "Unlike the robber barons of the United States 100 years ago, these people have not built empires out of nothing. They have accumulated large assets through a variety of creative ways. But the Rockefellers and Carnegies built where industry didn't exist."

The Russian barons have little tolerance for competition. Dmitri Ponomarev, president of the Russian Trading System, the country's electronic over-the-counter stock trading system, said many businessmen still retain the monopolist mentality of the Soviet era. "From the very beginning, they are thinking about `empire,' about dominating the whole market," he said.

"There is a lack of culture of trying to live with competitors. In most cases, they think not about trying to develop their business by market means, to develop their business to be in first place -- but only by eliminating competitors," he said.

James Fenkner, managing director of CentreInvest Capital Management, an investment fund, said, "Fortunes weren't made here by coming up with a better mousetrap. None of the richest people in Russia have developed a better mousetrap. What new has been created? Nothing. It's consolidation. It's slicing and dicing."

`Jurassic Park'

In Fenkner's office, the flashing computer screen is cluttered with prices, charts and graphs, financial trends and news flashes. This is the Russian Trading System, which lists more than 300 securities, about 70 percent of all those traded in Russia.

The market is young, relatively small and dominated by large monopolies and industrial behemoths that grew out of the Soviet era.

Fenkner described the market as a "Jurassic Park" where only the biggest dinosaurs roam. Many of Russia's newly profitable businesses are not found there, the "equivalent of omitting mammals from an account of life on Earth," Fenkner wrote recently. The stock market is overshadowed by oil and gas, telephone and energy companies that account for 91 percent of the capital. The remaining companies are banks, 5 percent; metals, 3 percent; and vehicle manufacturers, 1 percent.

Yet, Russia has some 14,000 mid-size companies created as a result of privatization, many of them starving for capital. Most are not found on the stock market. Fenkner said that investors -- especially the influential foreign investors -- aren't interested in small companies, which often have opaque balance sheets or old-fashioned Soviet "red directors" in charge.

Ponomarev, president of the stock exchange, said many smaller Russian entrepreneurs don't know how to raise capital. They don't want to give up control in exchange for investment, he said. At the same time, individual investors don't yet exist; most personal savings in Russia are still squirreled away under the mattress, or deposited in the state savings bank.

Nor have the Russian banks offered to take risks on the smaller companies. Over the last four years, the banks wallowed in profits from ruble-dollar speculation, and after that came high-yielding, tax-free government bonds known as GKOs. Banks simply did not give long-term loans to business. According to the Central Bank, Russian bank assets total $155 billion, but last year banks lent only $9 billion to enterprises.

Chubais declared recently that the Russian reformers wanted to create "laws which are one and the same for banks with a turnover of $1 billion and small family businesses with a turnover of $1,700."

But the reality is far different. After a spurt in small businesses several years ago, the number of such firms has leveled off. Irina Khakamada, the small-business chief in the Russian government, ticked off the reasons why: taxes, lack of capital, bureaucrats, crime. "I can tell you openly," she said, "that in the system of priorities among the economic and political elites in Russia, small business occupies the last place."

Trusova, the bakery owner, has learned that firsthand. A onetime engineer who was on the cutting edge of the early privatization, Trusova, 43, has never even thought about borrowing money from a bank, she said, because the rates are too high. Sales are falling, undercut by street vendors with no overhead. And she waits at the door for the next inspector.

In a letter to other small-business owners, she recalled that once a team of inspectors was "driving by the store, and a single lamp was not burning in the window. A fine. They approach the store, and there's a cigarette butt lying there. A fine. The salesperson was not wearing a cap. A fine. And they found dust on the lamp in the storage room, a fine. They wrote out a pile of fines and walked out of the store, happy!"

"They come to me once. They come to me twice," she said in an interview. "They've already taken everything, and I say, `How many times can you run to me?' Leave me something! Or else I simply won't be here." – notes Washington Post Foreign Service in the article “Russia's `People's Capitalism' Benefiting Only the Elite”