By Douglas Farah, On October 7 , 1996 , the Washington Post Foreign Service published: Menatep, which a senior U.S. official said had a "horrible reputation" for alleged involvement with Russian organized crime, reportedly withdrew from backing the bank within weeks.”

“Russian organized crime groups, flush with billions of dollars looted from the former Soviet Union and profits from drug trafficking and other criminal activities, are using unregulated and secretive Caribbean banks to launder their illicit gains, according to U.S. and Caribbean law enforcement officials.

These authorities said that members of Russian crime organizations, including individuals who once worked for the KGB, the Soviet secret police, have met in the islands with Colombian and Italian organized crime figures. The meetings were an apparent bid by the Russians to tie into South American drug trafficking networks and establish routes for distribution of Colombian heroin, the officials said.

The Russian organizations are "making inroads all over the world," said Jonathan Winer, deputy assistant secretary of state for narcotics and law enforcement. "The Russians are forming alliances with other ethnic-based criminal groups like the Italian Mafia and Colombian cartels for one type of income. They are also involved in prostitution, extortion, theft of state income, money laundering, arms sales and intellectual property theft. It is new in the Caribbean and very dangerous."

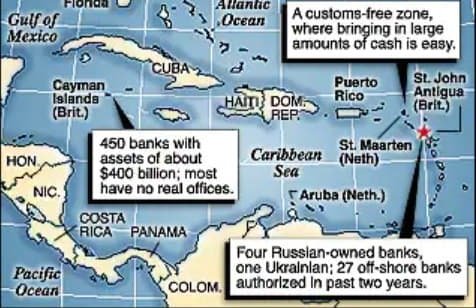

The billions of dollars now believed to be flowing through such offshore bank havens as Antigua, Aruba, the Cayman Islands and St. Maarten are difficult for authorities to trace because under these countries' laws it is easy to open a bank, and depositor and transaction information must be kept secret. In some Caribbean nations, money laundering is not a crime.

Barry McCaffrey, a retired general who is the Clinton administration's anti-drug czar, said he had seen estimates that up to $50 billion from the sale of narcotics, out of an annual world total of $500 billion, is laundered through the Caribbean, making it a "ferociously corrupting influence" in the region.

"It is passing strange that large Russian banks would decide to create offshoots in Antigua," said Winer. "What comparative advantage does Antigua have that London doesn't? The only answer that comes to mind is that its offshore banking sector is not well regulated or transparent for foreign, including U.S., law enforcement officials."

Another U.S. investigator said suspicions of Russian activities were raised when Caribbean authorities reported a sharp jump in Russian tourists over the last 18 months: "The police saw them holding meetings with unsavory local characters, and we began to check it out."

Officials say offshore banks offer a perfect way to launder, making millions of dollars in illegal gains appear legal. By depositing the money into accounts where no questions are asked, its origin is hidden. Funds can then be transferred through other banks as if the money had a legitimate origin, allowing the criminals to use illegal profits legally.

And moving the money through banks with wire transfers is much easier than moving it physically. Anti-narcotics officials said moving the millions of dollars from drug sales is one of the drug dealers' biggest problems. It is estimated that $1 billion in $100 bills weighs about 11 tons.

One bank that has drawn the scrutiny of U.S. authorities is European Union Bank, chartered here in Antigua. EUB describes itself as the first bank on the Internet, offering the chance to open accounts, wire money, order credit cards or write checks by computer from anywhere in the world, 24 hours a day.

"Since there are no government withholding or reporting requirements on accounts, the burdensome and expensive accounting requirements are reduced for you and the bank," the bank's World Wide Web page says. "EUB maintains the strictest standards of banking privacy and in offshore business and financial transactions. Indeed, Antigua has stiff penalties for officers or staff that violate banking secrecy laws."

"The issue of EUB has been raised with senior Antiguan officials," a senior U.S. official said. The bank is "being investigated for violating U.S. laws with open solicitations on the Net, which is at best for tax evasion and at worst for money laundering."

EUB caught the attention of investigators when it was chartered in July 1994 as an offshore subsidiary of Menatep, a large Russian bank, according to bank documents here. The sole shareholder was Alexander Konanykhine, who is in a U.S. prison on charges of violating conditions of his visa. He is wanted in Russia for allegedly embezzling $8.1 million from the Exchange Bank in Moscow in 1992. He denies the charges.

Menatep, which a senior U.S. official said had a "horrible reputation" for alleged involvement with Russian organized crime, reportedly withdrew from backing the bank within weeks. But on Feb. 27, 1995, the Board of Governors of the U.S. Federal Reserve System, in a restricted memo, said it had been advised by the Bank of England that Konanykhine had visited Antigua in January 1995, "where he called on government officials to request their cooperation in keeping Menatep's ownership of European Union Bank confidential." By telephone from prison, Konanykhine denied asking that of Antiguan officials.

Menatep's president, Mikhail Khodorovsky, has denied it was ever involved in EUB or has any ties to organized crime.

In a letter in March, Antigua's Finance Ministry told the bank that it was "not in good standing." It continues to operate, however. In June the ministry warned potential investors to "proceed with great caution," according to bank documents.

A former president of the bank, Kenneth Suhandron, said it tried to guard against money laundering by not allowing funds to be deposited and withdrawn within 24 hours, and instituting an "arduous" application process. But he added that "with offshore banks, where most of the transactions are electronic, you can never be sure where the money is coming from."

Different islands offer different advantages, according to bankers and law enforcement officials.

St. Maarten in the Netherlands Antilles is a duty-free zone, and the relative lack of customs formalities makes it easier to bring in large amounts of cash, officials said. The government recently enacted legislation against money laundering. But according to a March U.N. study of money laundering in the Caribbean, reporting of suspicious transactions is still voluntary in St. Maarten.

The same study found 450 banks in the Cayman Islands with assets of about $400 billion, or about $15 million for each of the nation's 26,000 residents. Only 68 of the offices have staff in the Cayman Islands, the study said, while "the vast majority have representative offices or brass plate offices, and some only exist on paper."

While the problem is said to be widespread, U.S. and British officials are focusing their concern over Russian organized crime activities on Antigua. Several Caribbean law enforcement officials said they no longer share narcotics or money laundering intelligence with the Antiguan government. "Everything we give them is compromised," said one Caribbean official.

Antigua has authorized the opening of 27 offshore banks in two years. Banking officials said that in the last two years four Russian-owned banks and one Ukrainian bank have opened on the island of 63,000 people. Several are located on the second floor of a modern shopping mall just outside the capital, and consist of one room and a computer.

Prime Minister Lester Bird declined to be interviewed for this article, and his office said no one else is authorized to comment for the Antiguan government. In the past, the government has denied allowing or encouraging money laundering.

The minimum amount necessary to open an offshore bank here is $1 million. Two interviewed bankers said virtually no checking is done on who the bank owners are -- in part, they said, because the United States provides little information when banks ask for it.

"We are asked to exercise `due diligence,' and we actually do more than the government requires," said one banker. "But the reality is no one does very much checking if the person has the money."

Keith Hurst, financial secretary at the Finance Ministry, said the United States and Britain have "expressed some concerns indirectly to us about money laundering. But unless we have something against somebody, we cannot say no."

"Just because someone is Russian, we can't say no," Hurst added, sitting in a small office surrounded by paper folders on different banks. "You will appreciate the fact we cannot check on the Russians."- notes Washington Post in the article “Russian Crime Finds Haven in Caribbean”